| Major Groups > Polypores > Lenzites betulinus |

|

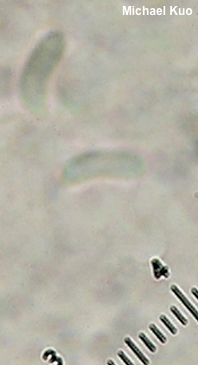

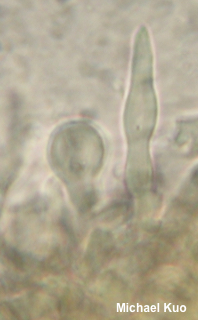

[ Basidiomycota > Polyporales > Polyporaceae > Lenzites . . . ] Lenzites betulinus by Michael Kuo, 4 March 2024 From above, Lenzites betulinus looks for all the world like Trametes versicolor or Trametes hirsuta, with its fuzzy, zoned cap. But flip it over and you will find that this little polypore has gills! We're talking true gills here, not the maze-like or "nearly gill-like" pores of polypores like Daedaleopsis confragosa and similar mushrooms. If the notion of a polypore with gills strikes you as oxymoronic, I can't argue with you—but see the essay below, "What, If Anything, Is a Gilled Mushroom?" Distinguishing Lenzites betulinus from similar mushrooms is a fairly easy matter. It has white, non-bruising gills and white flesh that does not change color, or turns merely yellowish, when a drop of KOH is applied; look-alikes differ on one or more of these characters. Gloeophyllum sepiarium has rusty brown flesh that turns black with KOH; Daedaleopsis confragosa has "gills" that bruise red when fresh and are usually more slot-like than gill-like, as well as flesh that turns gray to black with KOH; Daedalea quercina has thick, maze-like gills and turns black with KOH. Lenzites betulina is an "orthographic variant" for the same mushroom. Usually this means that the original author of the name screwed up the Latin agreement so we have to accept both the correct and original, incorrect endings. Some DNA studies (Tomsovsky et al. 2006, Justo & Hibbett 2011, Carlson et al. 2014) have placed Lenzites betulinus in a group alongside Trametes gibbosa—but separate from many other Trametes species. Depending on what is done with the many species of Trametes and with several other closely related genera (including Coriolopsis, Cubamyces, Leiotrametes, and Pycnoporus), the name Trametes betulina might be reasonably applied to Lenzites betulinus. Description: Ecology: Saprobic on the deadwood of hardwoods (occasionally reported on the wood of conifers); annual; growing alone or in overlapping clusters on logs and stumps; producing a straw-colored white rot of the sapwood; summer and fall; originally described from Sweden (Linnaeus 1753); widely distributed in Eurasia, Oceania, Africa, and the Americas. The illustrated and described collections are from Kentucky, Ohio, and Texas. Cap: 1–10 cm across; semicircular, irregularly bracket-shaped, or kidney-shaped (or nearly circular when pendant from branches); flattened-convex; flexible; densely velvety-hairy, with concentric zones of texture; often radially bumpy or ridged; with zones of whitish, grayish, brown, and cinnamon colors—and sometimes developing greenish colors in old age as a result of algae. Gills: Well-spaced or fairly close; sharp; tough; short-gills frequent; whitish, becoming ivory with age; not bruising; up to 1 cm or more deep. Stem: Absent. Flesh: White; not changing when sliced; extremely tough and corky. Odor: Not distinctive, or slightly fragrant. Chemical Reactions: KOH negative to yellowish on flesh, cap, and gills. Spore Print: White. Microscopic Features: Spores 5–6 x 1.5–2.5 µm; allantoid; smooth; hyaline in KOH; inamyloid. Basidia 15–20 x 6–8 µm; clavate; 4-sterigmate. True cystidia not found (but see below). Hyphal system trimitic. Binding hyphae 4–10 µm wide; smooth; thick-walled; hyaline in KOH; hyphal tips ranging from merely rounded to subacute or acute—sometimes projecting through the hymenial palisade, appearing like cystidia. REFERENCES: (C. Linnaeus, 1753) E. M. Fries, 1838. (Murrill, 1908; Overholts, 1953; Phillips, 1981; Smith, Smith & Weber, 1981; Arora, 1986; Breitenbach & Kränzlin, 1986; Gilbertson & Ryvarden, 1987; Phillips, 1991/2005; Schalkwijk-Barendsen, 1991; Lincoff, 1992; Barron, 1999; McNeil, 2006; Tomsovsky et al., 2006; Binion et al., 2008; Boccardo et al., 2008; Kuo & Methven, 2010; Justo & Hibbett, 2011; Buczacki et al., 2013; Carlson et al., 2014; Kuo & Methven, 2014; Desjardin, Wood & Stevens, 2015; Siegel & Schwarz, 2016; Baroni, 2017; Ginns, 2017; Woehrel & Light, 2017; Elliott & Stephenson, 2018; Læssøe & Petersen, 2019; Kibby, 2020; McKnight et al., 2021.) Herb. Kuo 10010405, 10200701, 02192401. This site contains no information about the edibility or toxicity of mushrooms. What, If Anything, Is a Gilled Mushroom? In the title to a notorious paper, A. E. Wood (1957) asks: "What, If Anything, Is a Rabbit?" At issue is whether or not the label "rabbit" actually refers to anything scientifically coherent—to a group of organisms, say, that are related and share features that are not shared with other groups. Wood concludes that "rabbit" probably is a term with some scientific meaning, but a more recent essay by S. J. Gould (1983) entitled "What, if Anything, Is a Zebra?" summarizes fairly convincing evidence that there is no such thing as a "zebra," from a scientific standpoint consistent with evolution. In short, the evidence is this: there are three species of zebras, and two of them are more closely related to horses than they are to the third zebra species—which means that the two groups of zebras evolved their stripes independently, since horses have no stripes. Lenzites betulinus demonstrates that the question "What, If Anything, Is a Gilled Mushroom?" is worthy of consideration. It is a gilled mushroom in the polypore order, Polyporales, which diverged from the gilled mushrooms, the Agaricales, many eons ago. In other words, there is no such thing as a "gilled mushroom" if, in applying the term, we want to convey a sense of how mushrooms are related, since Lenzites developed its gills independently, irrespective of gill development on other branches of the mushroom evolutionary tree. In general, two reasonable scientific answers have been provided to explain examples of "convergent evolution" like the stripes on "zebras" or the gills on Lenzites betulinus (a third answer, that convergent evolution reflects evidence of a Designer's Grand Plan, is neither reasonable nor scientific). One set of answers maintains that the common ancestor of the organisms in question carried the genetic potential for the feature (gills, in our example), and that the separate evolutionary lines, having inherited this potential, later expressed it. A second set of answers, not necessarily in conflict with the first set, maintains that the forms available to an organism are necessarily constrained by the laws of earthly physics (gravity, light, and so on), so that evolutionary forms cannot just develop willy-nilly, but must fall within a limited set of physics-bound possibilities in order to succeed. To be rigorously accurate, there are many more than "two" kinds of scientific answers to the question of what constraints are involved with natural selection and evolution, and the matter is far from being settled among biologists. It appears that both genetic potential and physical constraints are indeed involved--but other factors, including random genetic "drift," are also apparently operative. For a thorough account of current biological thinking about these questions, I recommend Massimo Pigliucci's "Finding the Way in Phenotypic Space" (2007, full citation below). |

© MushroomExpert.Com |

|

But the term "gilled mushroom," as any mushroom hunter knows, is perfectly valid as a way of describing and identifying mushrooms, regardless of whether it represents a coherent scientific term. And it should be pointed out that in the case of Lenzites betulinus we cannot blame the "DNA Revolution" for the mess we are in when it comes to classifying (as opposed to identifying) the mushroom; we have thought of it as a "gilled polypore" for centuries, and any mushroomer who sees the thing in the woods is likely to reach the same conclusion. DNA studies have merely verified (for once) our previous observations—which leads us to another question: "What, if anything, is a polypore?" If it is the case that just about any mushroomer is likely to look at Lenzites betulinus and decide it is a polypore despite its gills, what is the operative and probably subconscious definition of a "polypore?" It obviously isn't the presence of pores! References Gould, S. J. (1983). What, if anything, is a zebra? In Hen's teeth and horse's toes: further reflections in natural history. New York: Norton, pp. 355–365. Pigliucci, M. (2007). Finding the way in phenotypic space: the origin and maintenance of constraints on organismal form. Annals of Botany 100: 433–438. Wood, A. E. (1957). What, if anything, is a rabbit? Evolution 11: 417–425. Cite this page as: Kuo, M. (2024, March). Lenzites betulinus. Retrieved from the MushroomExpert.Com Web site: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/lenzites_betulinus.html |